In the ever-evolving cultural landscape, the way we perceive and engage with memory institutions is undergoing a profound transformation. Our recently published scholarly work, titled “Rethinking GLAMs as commons: a conceptual framework”, introduces a fresh perceptive on Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (GLAMs), framing them as potential commons – shared spaces produced and managed by their communities[1].

GLAMs and their professionals have traditionally been viewed as the main custodians of knowledge and our common heritage. However, demands for greater democratization and participation in the sector today challenge this conventional understanding. Professionals need to examine further their roles as facilitators of community-driven narratives, encouraging inclusivity, and fostering a sense of shared ownership among the public. At the same time, more and more local commons-oriented initiatives are popping up in urban as well as in rural and peripheral areas in the EU, like neighbourhood libraries, oral history groups and archives, local community museums, etc.

Drawing inspiration from the “new commons”, we argue that GLAMs can be reconceptualized as commons-like institutions; spaces that can be collectively owned, managed, and sustained by their communities. This shift in perspective emphasises the participatory role of the public and its importance in shaping the purpose of memory institutions and safeguarding their sustainability in the current socio-economic landscape.

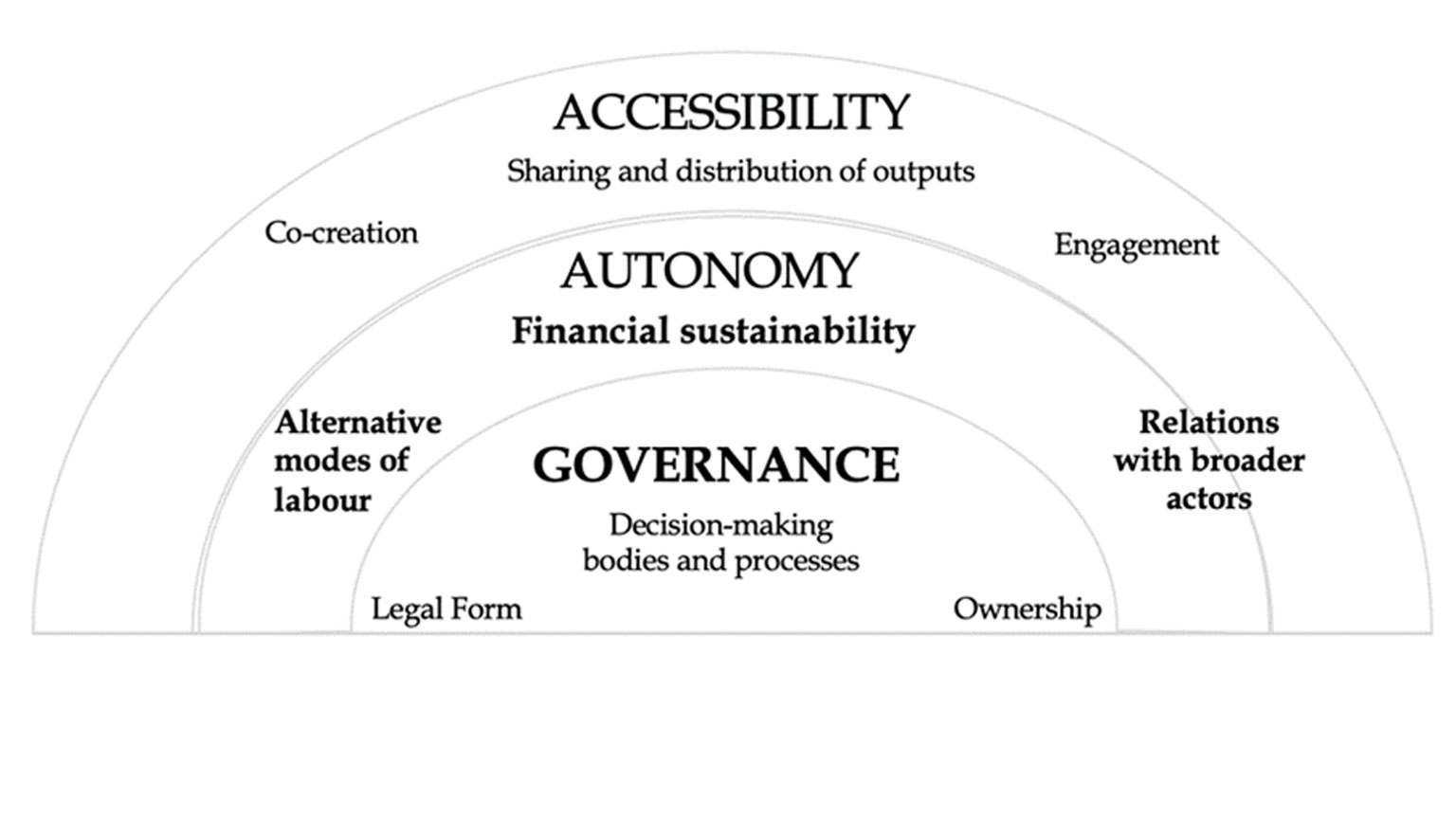

Figure 1: The different layers of GLAMs as commons, as conceptualised in Avdikos et al.

How do we conceptualise GLAMs as commons? Or where do we find commoning practices in GLAMs?

Figure 1 outlines three levels where commoning practices are performed. Commons-oriented GLAMs usually have a horizontal decision-making process that entails assemblies of the community, while the community owns the archive, library or the museum. The legal forms usually implemented in such organisations are associations, cooperatives, charities, etc. The next level is the one where most of the challenges in GLAMs’ operations are found. And this is the level of securing the autonomy of the organisation against dependencies from market forces (private donors/patrons) or the state. Commons-oriented GLAMs need to find the right balance to secure the resources that are needed for the organisation to keep performing, while maintaining relations with the market and the state. Many commons-oriented GLAMs attempt to secure their autonomy by relying on volunteering labour from their community, while others attempt to secure resources also through networks with other commons initiatives (e.g. urban commons, digital commons). The third level is the level of openness and accessibility of the organisation, where we find co-creation processes and an augmented possibility for the audiences to actively participate in shaping the outputs, through co-exhibitions, etc., that is, for the audiences to transform from audiences to participants.

Are all the above levels to be found in most of GLAMs? Probably not; there are not that many organisations that operate as commons-GLAMs per se, but there are a lot of GLAMs which have internalized and currently use commoning practices from all these three levels. A key difference is the ‘location’ of these commoning practices and whether these give an advanced role to the community to decide upon the matters that are most crucial for the organisation. Usually, smaller and community-oriented GLAMs may have greater flexibility in adopting commons-like governance, whereas bigger organisations (e.g. public sector institutions, or private entities) usually engage with co-creation commoning practices through digitalisation processes and citizen/community participation. One implication of mapping commons practices and their ‘entry points’ is providing GLAMs’ professionals with resources which could aid in promoting the proliferation and expansion of commoning practices within cultural organisations.

Overall, our conceptual framework challenges us to reimagine GLAMs as dynamic, participatory commons which thrive on community engagement and enable this engagement to become more meaningful participation. This fresh perspective invites heritage and culture professionals to further help unlocking the past in a way that truly belongs to the present and its people.

At the same time, the application of such practices shows us that we need to rethink the ways in which the state and public sector can assist such commons arrangements. The public sector should assist such initiatives through the provision of a supportive institutional and legal framework, which could further enable commoning practices (for instance, through social and solidarity economy legal forms), and funding schemes (or the provision of some basic infrastructure, like cloud storage) that can be effectively used in commons arrangements and can assist these organisations in responding to their main challenges.

[1] Avdikos, Vasilis, Mina Dragouni, Martha Michailidou, and Dimitris Pettas. “Rethinking GLAMs as commons: a conceptual framework.” Open Research Europe 3, no. 157 (2023): 157, https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.16473.1